Notes from Antrim Plateau

Day 1.

I arrived in Belfast last night by ferry, and went straight to the B&B I’d booked. Basically it was a comfortable cupboard with a shower and Netflix - not really a B&B, unless a biscuit and some chocolate buttons really counts. After a very solid sleep, I stepped out this morning onto the streets of East Belfast. I’ve never been to the city before and wish I’d had more time to explore, but I was being pulled out of Belfast and towards the nearest curlews.

After one of the tastiest vegan breakfasts I’ve ever had (at a place called the Lamppost Cafe) I took a train out to Antrim, where I was picked up by my next B&B host, Jane - an incredibly warm and welcoming lady, in her sixties or possibly early seventies. Motherly, in a ‘no-nonsense’ kind of way. I sensed an inner strength gained from a life well-lived. It’s a real B&B this time - a farmhouse with practically hotel-level service, a king size bed and rooms with walls about three metres thick, which made me feel like a precious stone in a heavy safe (at least after I’d showered). I suddenly felt less inclined to go and record curlews before bed - especially with some dodgy weather reportedly on the horizon.

I made a deal with Jane: she’s going to drive me out to Glenwherry (where the curlews are) tomorrow morning, and, in exchange, I’ve taken some quality photos of the farmhouse to help her tempt further visitors. There are no curlews here anymore, but there are sheep, dogs and chickens (one of which may be dying). Oh - and there are a couple of rogue goats wandering around outside, one of which has the neck strength of a wildebeest, as I learned from trying to lovingly scratch its head. I grew up surrounded by goats, so I feel at home here. Before bed I sat down and had a long chat with Jane, who helped to fill in some gaps in my knowledge of northern Irish politics (I’m discovering there are more than I realised) and guided me through her own fascinating family history.

Beech Lane Farmhouse B&B - home for two nights

Day 2.

This morning, following a tasty cooked breakfast, Jane (who’d also prepared a flask of tea for me and wrapped some cake in foil) drove me to Glenwherry. When we arrived at the precise location that had been given to me by the local Curlew LIFE Project Officer, Katie Gibb, I got out of the car and caught my first glimpse of the magical Slemish Mountain. According to legend, St Patrick worked on Slemish as a shepherd for about six years. When exactly that was supposed to have been suddenly didn’t matter. The Antrim Plateau has a primordial feel. As the RSPB’s Neal Warnock puts it, it feels like “a land that time forgot”. Katie, who was rushing off to a meeting, welcomed me and pointed me in the direction of a white van, belonging to research assistant Annie Birtwhistle. I made my way up a long track towards Annie and her van, catching little snatches of curlew sounds on the breeze.

After some quick introductions, Annie and I realised that we have a few things in common. While she grew up in rural Ireland and I in Orkney, we both have predominantly English accents due to being ‘home-schooled’ by our English parents, and growing up relatively isolated from other humans. Annie, who needed to move some fence posts, guided me towards who she and Katie call the ‘Douglas Weirdos’ - a group of curlews, named partly after a nearby road, and partly after their strange behaviour. This seemed to be another example of failed breeders hanging out and finding ways to entertain themselves. I found a comfortable tree and settled down on its roots, sheltered a little from the warm wind with my flask and a few precious caramel wafers. It wasn’t long before the Douglas Weirdos turned up. As well as chasing each other and engaging in some interesting aerial acrobatics, they also landed close by and uttered some weird, croaky noises. I’d been sitting there for about 30 minutes when Annie returned, liberated from her fence posts. She had to go and check that some curlew chicks under observation hadn’t strayed into a nearby silage field that was due to be cut by the farmer tomorrow, so I asked if I could follow. Not for the first time on these expeditions, I was required to face my fear of cows and walk through another field of them. One more chance for truth and reconciliation? Apparently not, given that they decided to play their favourite game of slowly encircling you, running away just when you’ve accepted that they’re probably about to trample you into the earth’s crust, and then turning around and starting all over again. We reached the other side and I gratefully jumped the wall and into another field containing a bull. Despite having a face like a furry Mike Tyson, he was docile and uninterested in terrorising me further.

Waiting for the Douglas Weirdos

A very close working relationship seems to have been developed on the Antrim Plateau between the RSPB and local farmers - something that needs to be replicated elsewhere if possible. The RSPB’s ambitious aim over the Curlew LIFE project’s five sites (Antrim Plateau being one of them) is to achieve breeding stability for curlews within five years. Even if successful, these tiny pockets of protection will not be enough if we’re serious about reversing the decline of curlews. What they can do though is provide a template for curlew and wildlife-friendly land use, which can then be carried out and applied to the wider countryside. From what I’ve witnessed at sites throughout the country, building positive relationships between the RSPB and local farmers is vitally important.

In Glenwherry, where Annie and I found ourselves today, the local farmer had offered to delay cutting his field if the chicks had strayed into it. It just goes to show that it is possible to work together and balance different priorities between people and nature, to the benefit of both (an idea at the heart of all good ‘rewilding’ projects). That’s how we found ourselves crouched under a tree, surrounded by nettles. While Annie tried to locate the chicks, I recorded the adults as they flew and called close by. In moments of quiet, we talked about all sorts of things, spanning biology, culture and politics. One of the privileges of these recording trips has been the chance to ‘slow-meet’ people in a way at odds with how we usually live our modern lives. It’s rare to have an entire day to get to know someone, in a context where long breaks in conversation feel completely natural. Unaware of our presence, Mistle Thrushes flew into the branches above and swarms of flies buzzed around the microphone. Once Annie was confident that the chicks weren’t in the silage field (she didn’t actually see them but was able to garner clues from the parent’s behaviour), we made our way back to the track and had a quick break before dusk recording began.

Annie and Katie

Katie soon returned, clutching a heavy glass bowl filled with tadpoles, rushes and chunks of cucumber. She’d rescued them (the tadpoles, not the chunks of cucumber) from a shrinking pool and, and gave me the task of holding this special aquarium while we searched for a new damp habitat for them. With the tadpoles safely delivered to a ditch, we set off to another part of Glenwherry. Katie and Annie became intrigued by an irate curlew whose behaviour suggested it might have a nest or chicks, although their scepticism hinted at the illusory nature of many previous encounters. I thought again of D.H. Hudson’s description of curlews as “half bird, half spirit”. Curlews are just as slippery as tadpoles in their own way. Despite one very vocal curlew and the wonderful whirring of Common Grasshopper Warblers, this site was closer to a main road, so we decided to head back to where we started as dusk closed in.

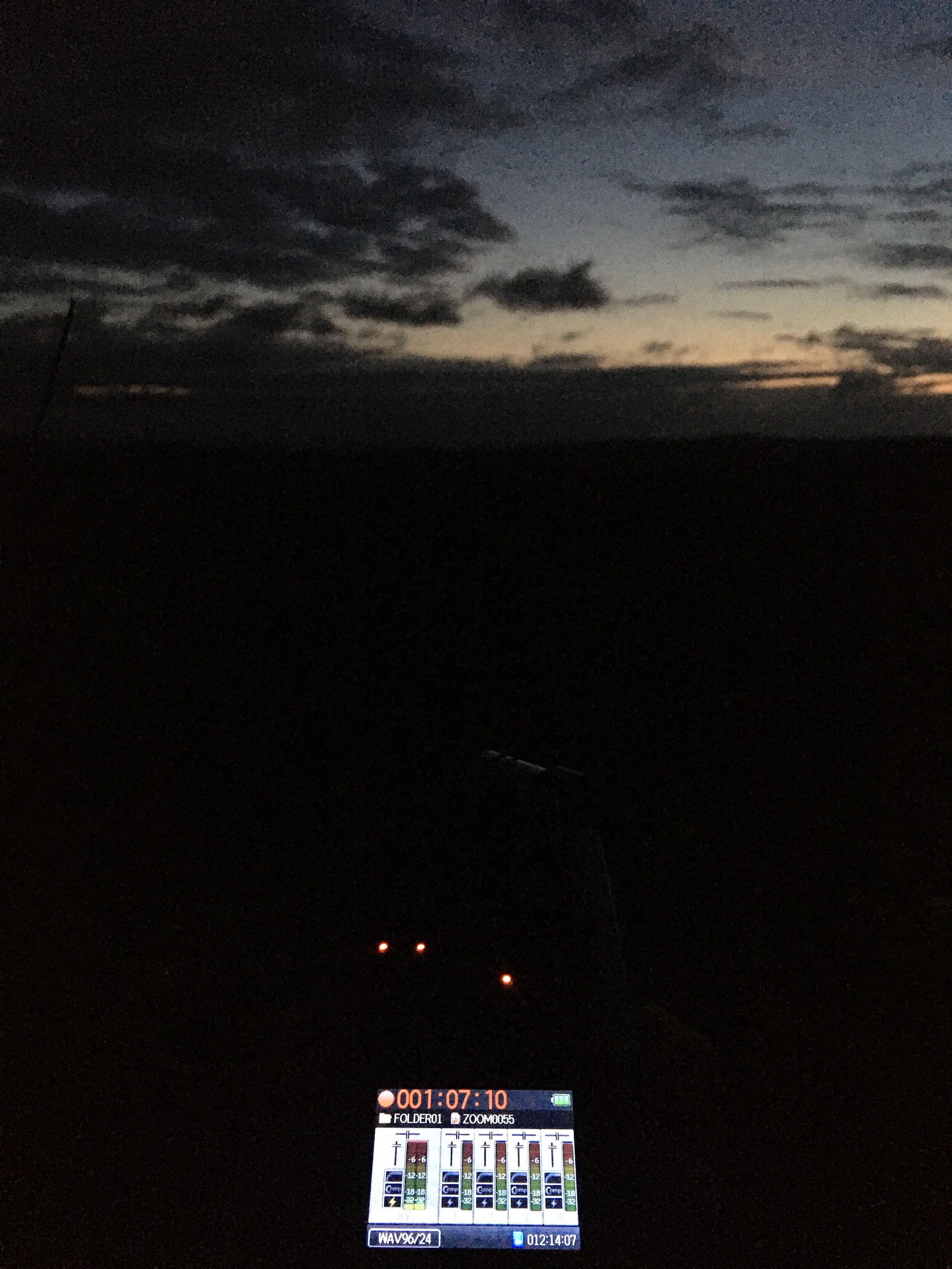

Night falls on Slemish Mountain

This time we walked further up the track, beyond the Douglas Weirdos and towards a few curlew pairs and their chicks. What came next was pure joy. The weather was flat calm, the air cool and the new moon as thin as a curlew’s bill (part of the curlew’s Latin name, numenius, means “of the new moon”). With the last of the sunset’s peachy-pinkness clinging to the horizon, snipe came out in force, drumming above us and ‘chipping’ from the ground. A sheep coughed like a human. Before long, as if they knew I’d been waiting for them, eerie nocturnal curlew sounds joined the soundscape. After some initial contact calls (“curleeee”, followed by something a bit like a bubbling call), one of the adults started making an alarm call that none of us had heard before - a strange, single short stabbing sound, repeated over many minutes. We wondered whether this was a special nocturnal alarm call. It’s strangely satisfying how we still don’t know so much about a bird that’s been around for thousands of years. Just before we packed up, I put the microphone down and joined Katie and Annie, sitting in silence and staring out into the twilight. All that was missing were a few beers.

Many thanks to the RSPB’s Katie Gibb, Annie Birtwhistle and Neal Warnock in Antrim. A big thanks also to Jane at Beech Lane Farmhouse for your great hospitality (RIP Jane’s hen, which has sadly now passed on) - I hope your new photos bring you many more guests!